The European civilisation subjugated and humiliated by the onslaught of Islamist hordes, the forced conversions, the public executions in the squares, the burning of “profane” books, all this to the accompaniment of a plangent summons of a muezzin up in the minaret of a gigantic mosque erected on the site of the torn-down Notre Dame de Paris… If this is how you imagine the new novel by Michel Houellebecq, my advice is: spare the money and buy some science fiction dystopia dealing with the subject instead. I guess there should be something on the market these days. At the end of the day, Submission is not so much about the dreaded islamisation of Europe, as it is about the problem of getting laid for the man on the wrong side of forty. Just like the rest of Houellebecq’s works, n’est-ce pas?

Submission is a breezy read and ideal fodder for the hungover reviewer recuperating from a spell of overindulgency during the Christmas and New Year holidays. What I like about Houellebecq is that his books don’t send me to the dictionary too often, a fancy phrase or an abstruse word is not the hallmark of his rather pedestrian writing style. It’s opinions, observations, and once again opinions, which matter the most when one opens any of his books.

To get it out of my system from the very outset, I will allow myself the luxury of alluding to Karl Marx’s oft-quoted statement about historical facts occurring the first time as tragedy, and the second as farce. In case of Houellebecq, there is a farce at the beginning, and genuine ennui the second time. Yes, he does it again. In his new novel he rips off whole sentences (sometimes with minor alterations) from French Wikipedia, just the way he did in his Prix Goncourt winning The Map and the Territory . You surely must remember the debate about his borrowings from the free encyclopedia in the previous novel. This time he steals from the article about the Greek mythological prophet Casandra. Maybe there is more, but, for the life of me, I couldn’t bother to check further. With his Submission, Houellebecq seems to have fully (excuse the awful pun) submitted to the cliché-ridden concept of what a typical Houellebecq novel should be like. He ticks all the boxes, knowing quite well, that it is exactly what his numerous readers crave for.

The novel is set in 2022. The protagonist of Submission is a 44-year old professor of literature at Sorbonne called François. He is a specialist in K. J. Huysmans, giving lectures on 19th century French literature and occasionally publishing articles in the scholarly magazine Journal des dix-neuviémistes. After a succession of various affairs with the female students at the university (first as a fellow-student, then as an instructor) he finds his ability to experience sexual pleasure on the wane and starts spending more time masturbating to online pornography. He is bitter, callous, cynical, frustrated, a bit of a racist, quite a lot of a misogynist, … you name it.

François’s life radically changes after the Muslim candidate Mohammed Ben Abbes is elected president of France. This becomes possible because the Socialist Party, The Union for a Popular Movement and The Union of Democrats and Independents enter into a coalition with the Muslim Brotherhood (an imaginary party of French Muslims) to prevent the National Front from winning the elections. As a result of the agreement between the members of the coalition, François Bayrout (the current leader of the Democratic Movement in France) is appointed prime minister. From the very beginning it becomes apparent that he has no political weight of his own, his main role being to unconditionally support the new policy of the Muslim president. What is noteworthy, is that the Muslim Brotherhood is not so much interested in the economy of the country as in the demographics and education. The new government carries out major reforms in public schools and state universities. As a result, the main university in France gets renamed as the Islamic University of Paris-Sorbonne and is lavishly funded by the petrodollars of Saudi Arabia. Women lecturers are summarily dismissed, and all the female students have to wear the veil. As you can imagine, such a turn of events is unlikely to rejoice the middle-aged womanising academic. Of course, these changes are just part of the major political and cultural overhaul initiated by the new authorities. Being moderate Muslims, the Brotherhood do not do anything rash, at least not yet. The changes in the society are gradual, even subtle, but still quite considerable already in the first month of Mohammed Ben Abbes’ tenure.

François spends the turbulent change of the regime away from the rioting Paris in the town of Martel (ironically enough, near the site of the historic Battle of Tour in which the Muslim invasion of Europe was checked in 732) most of the time cut off from any information about what is going on in the capital. When he finally returns to Paris, it is the noticeable alterations in the female fashion which alert him to the fact that France is becoming a different country:

And the female clothes had changed; I felt it immediately, although failing to analyse this transformation. The number of Islamic veils had hardly increased; it wasn’t that, and it took me almost an hour of wandering to grasp all at once what had changed: all the women were wearing trousers. The detection of women’s thighs, the mental projection reconstructing the pussy at their crossing, the process whose power of excitement is directly proportional to the length of the naked legs: all this was in me so much involuntarily, automatic, genetic as it were, that I had not become aware of the fact immediately, but the evidence was there, dresses and skirts had disappeared. A new garment had also become widespread: a kind of long cotton blouse reaching the mid-thigh, which killed all the objective interest in skintight trousers certain women could have eventually worn. As for shorts, they were obviously out of the question. The contemplation of the female ass, a small dreamy consolation, had also become impossible.

Upon his return to Paris, François also learns that as a non-Muslim he has lost his position at the university. This might have been a cause for serious financial concern if the Saudi funding had not provided him with a pension of 3,472 Euros a month. For his colleagues who have chosen to convert so that they can teach at the new university, the situation has turned into something straight from One Thousand and One Nights: they start receiving a whopping 10,000-Euro monthly salary as well as obtaining beautiful young wives. As for François, his chances of finding a female companion are rather low at this point. The only mistress pool available to him, i. e. the female university students, has become inaccessible after his retirement. He has to resort to an Internet escort service after his Jewish girlfriend has left France for Israel — understandably enough, the prospect of living in a country ruled by Muslims has triggered a wave of Jewish emigration.

When François comes into rich inheritance left by his father, he realises that he does not have to work for a living any more. But the financial comfort and the opportunity to use prostitutes cannot completely satisfy the retired professor, as there is still smouldering need for scholarly accomplishment and genuine female interest. The former suddenly becomes possible thanks to the commission by the renowned Bibliothèque de la Pléiade to supervise the publication of the annotated collected works of Huysmans within the series. François jumps on the opportunity and starts preparing notes and the preface to this edition. While he is pursuing the task, we learn quite a lot about this writer and his life. One of the most significant moments in Huysmans’ biography is his sudden conversion to Catholicism which he later fictionalised in the second volume of the Durtal tetralogy. We cannot help but start realising that by revisiting Huysmans’ life and work in his editorial endeavour, François might be also on his way to conversion, although in his case it will not be Catholicism, that’s for sure.

When François pays a visit to the president of the Islamic University of Paris-Sorbonne, a Belgian convert called Robert Rediger, he accidentally runs into his teenage wife Aisha domestically dressed in a pair of jeans and a T-shirt. She is his second wife. Later he meets the first one, the forty-year old Malika who cooks exceptionally delicious puffed pastry. The physical merits of one wife and the culinary skills of the other make a lasting impression on the guest. During their conversation, Redeger provides a host of arguments in favour of Islam, even falling back on the major discoveries in astronomy and physics that, in his opinion, support the fact of the existence of the unique God. When the meeting is over, the president gives François his Ten Questions about Islam, a brief overview of the major principles of the religion. It is not surprising that, when later reading the little book, the main character finds the chapter discussing polygamy particularly interesting . The sight of the fifteen-year old Aisha with a shock of black hair, wearing jeans and a T-shirt is a strong argument that cannot be brushed aside easily. When the preface and the explanatory notes to the new edition of Huysmans’ works are finished, François receives a proposal to return to the university. He realises that at this point he will have to make one of the most important choices in his life.

Map of Eurabia

The personal drama of François develops on the background of important political transformations as the European Union slowly but surely starts accepting Muslim states into its fold. The first acceding countries are Morocco, Algeria, Turkey and Tunisia. Egypt and Lebanon are to join them in the near future. There have also been some initial contacts with Libya and Syria. One doesn’t need to have an exceptional geopolitical acumen to predict that at this rate in one generation Europe as we know it will cease to exist and will be transformed into a new Caliphate. In order to read what this political formation might be like, you will have to wait for Vladimir Sorokin’s Telluria to be translated. Submission does not look that far into the development of our civilisation. Which is just as well, because, when it comes to vivid descriptions of a dystopian future, Houellebecq is not the best author to turn to. In this novel the French writer manages to sum up some of the topical problems facing the European Union and to give scathing commentary on contemporary French politics. Whether one has to read a whole novel for that, is up for you to decide. Politics aside, Submission provides a convenient excursus into the life and works of K. J. Huysmans, convincingly making case for reading more of this writer. There are also interesting references to the poet Charles Pierre Péguy and his long Christian poem Eve which bemoans the decline and dissolution of humanity. The readers belonging to the academia will find a lot of nudging references to their internal problems and insecurities. And, surely, there are some pithy observations that are bound to be quoted by the media for the months to come, one of which is definitely the following:

It is an idea that I would hesitate to expose before my coreligionists, for they, perhaps, will consider it a bit blasphemous, but for me there is a relation between the absolute submission of the woman to man, such as described in Story of O

, and the submission of man to God, such as envisaged by Islam.

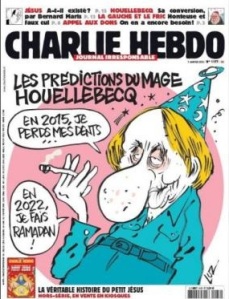

The publication of the novel coincided with the horrible massacre at Charlie Hebdo. The latest issue of the magazine featured a caricature of Houellebecq on its cover. As you might remember, in my post about the forthcoming publication of Submission, I expressed hope that it would not provoke aggression against the author on the part of Muslim radicals. Now that I have read the book, I do not think it will be the case. The novel turned out by far more tame than I could have expected. Most of the readers who have bought it anticipating loud confrontational statements against Islam will be most probably disappointed. Very indicative of this distanced attitude is Houellebecq’s recent interview to The Paris Review, in which he says:

The publication of the novel coincided with the horrible massacre at Charlie Hebdo. The latest issue of the magazine featured a caricature of Houellebecq on its cover. As you might remember, in my post about the forthcoming publication of Submission, I expressed hope that it would not provoke aggression against the author on the part of Muslim radicals. Now that I have read the book, I do not think it will be the case. The novel turned out by far more tame than I could have expected. Most of the readers who have bought it anticipating loud confrontational statements against Islam will be most probably disappointed. Very indicative of this distanced attitude is Houellebecq’s recent interview to The Paris Review, in which he says:

But I am not an intellectual. I don’t take sides, I defend no regime. I deny all responsibility, I claim utter irresponsibility—except when I discuss literature in my novels, then I am engaged as a literary critic. But essays are what change the world.

Indeed, when acting as a literary critic through the main character, Houellebecq shows his best in the novel. That is when the lukewarmness disappears, and he is utterly engrossed in the subject. Submission had hit the first place on the French Amazon bestseller list already two weeks prior to its publication and at the time of writing this review is firmly established in this position. It would be great if the works of J. K. Huysmans tangentially benefited from the predictable roaring success of Houellebecq’s admonition to Europe.